When are operators annoyed by the presence of a collaborative robot? When do they consider the robot as an effective collaborator?

These questions are fundamental in a human-robot collaboration scenario. Task 1.2 of the PICK-PLACE project analyzes the role of motion-planner behavior on the operator’s feelings.

An experimental campaign has been used to understand how humans are affected in their jobs by the presence of a robot. The results have been described in Deliverable 1.2. This post offers a brief summary of the most relevant conclusions.

1) Workspace-sharing scenario

In the first experiment, the user was asked to unscrew some screws from a metallic item. The path between the disassembly area and the screw buffer were inside the robot workspace but it did not intersect with any robot trajectories.

During the human task, the robot executed a repetitive pick-and-place motion. The robot changed the path or the velocity and acceleration profile.

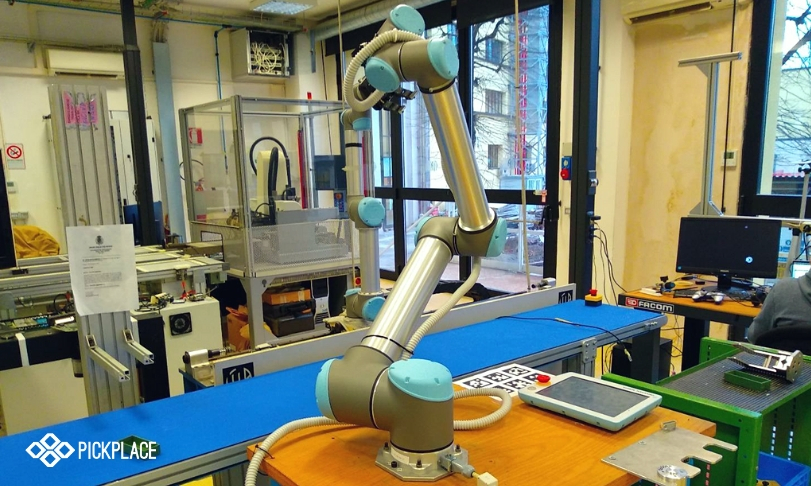

Figure 1: Experiment 1 layout. The blue circle is the disassembly station; red circle is the screw buffer.

1. How is human productivity altered by a robot’s presence during his/her activity? There is a correlation between human and robot throughput, also without a direct human-robot collaboration. In other words, if the robot moves slowly, the operator also decreases the throughput.

2. Is the human more distracted by path variations or speed variations? Unpredictable path changes hinder the operator more than unpredictable speed/acceleration changes.

3. How do humans modify their behavior when the robot is present? Humans overestimate robot distances, especially during predictable movements. Human path is not strongly influenced by the robot movements, if the robot path does not intercept the operator’s trajectory.

2) Direct human-robot collaboration scenario

The second experiment deals with a task that requires direct collaboration between robot and human. The user was asked to bring to the robot a tape and 10 screws. The tape and the screws were located on a worktable, therefore the human had to pick one or more of them and walk to the robot (see Figure 2). The robot performed a picking movement and closed the gripper finger to grasp the object, then placing the object in a buffer.

The human was asked to bring the screws to the robot in order to place them all inside the tape. The operator was informed that the number of screws inside the circle would be the evaluation score. However, this task was introduced only to focus on the user’s attention on a practical task instead of the robot movement.

In some experiments the robot movements were triggered by the operator position, in others the robot moved without caring about operator activities.

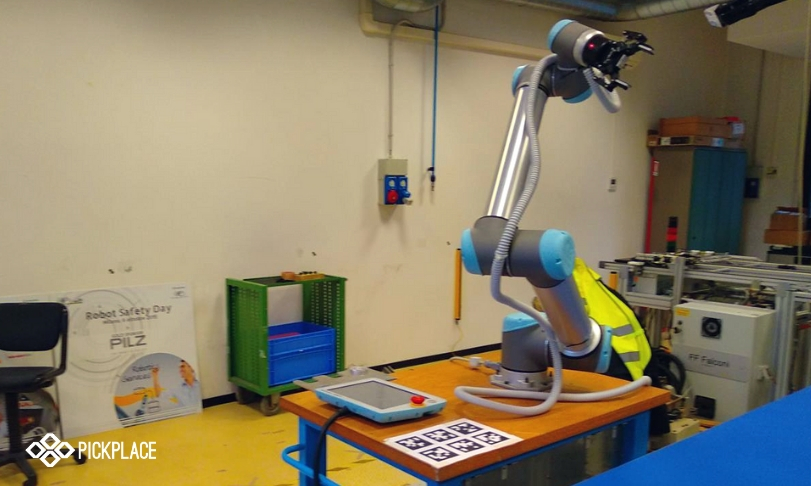

Figure 2: Experiment 2 setup. Blue circle: worktable. Red circle: Picking area.

1. Do acceleration changes influence human perception more than the velocity changes? Operator feels trajectory time is more important than speed and accelerations. Different motion profiles with the same total time are difficult to recognize when the operator focuses his/her attention on the task.

2. Do humans perceive human-robot collaboration as an improvement when they are the leader? Yes, humans consider the robot more collaborative when they can decide the cooperation activity timing.

Next steps

In Work Package 4, new offline and online motion planners algorithms are under development in order to obtain robot movements that are felt natural by the robot operator, especially by reducing unpredictability of the motion plan.